Three Revolutionary Watchmaking Inventions

Within the world of watchmaking we are treated to what seems like an endlessly long list of new inventions from watchmakers the world over. As brands constantly seek an edge over their competitors, the community is bombarded by seemingly revolutionary inventions. Still, the fact of the matter is that they aren't revolutionary – for the most part anyway. With that being said, however, every so often, those inventions are revolutionary, and the world of watchmaking becomes a little more advanced. Here, we will cover three watchmaking inventions that did actually cause a revolution, for better or for worse.

The Quartz Movement

Created in 1969 by Seiko, the quartz movement ushered in an unprecedented era for the watchmaking industry. Bringing the entire Swiss watchmaking industry to its knees, the Japanese-invented movement was cheaper and faster to produce, far more accurate than mechanical movements and reduced the barrier to entry for watchmakers by a considerable amount, basically overnight. This, mixed with the fact the technology was new, sent customers flocking from Swiss brands to Japanese competitors in search for their cheaper, technologically advanced and more accurate timepieces.

Working by passing an electrical current from a battery through a quartz crystal, quartz movements forgo mechanical energy storage like that stored in a mainspring in automatic or manual watches. The electrified quartz crystal vibrates at an exact frequency which can then be used to oscillate the movement and drive the motor, much like a balance wheel in a mechanical timepiece. As the frequency is known, the quartz movement will know to move the second hand once the crystal has oscillated 32768 times – indicating one second has passed.

Working by passing an electrical current from a battery through a quartz crystal, quartz movements forgo mechanical energy storage like that stored in a mainspring in automatic or manual watches. The electrified quartz crystal vibrates at an exact frequency which can then be used to oscillate the movement and drive the motor, much like a balance wheel in a mechanical timepiece. As the frequency is known, the quartz movement will know to move the second hand once the crystal has oscillated 32768 times – indicating one second has passed.  While quartz was only first released in 1969, Bulova released their Accutron model in 1960. This watch was powered by a precursor to the quartz movement, by passing a current through a tuning fork. It used this tuning fork to replace the traditional timekeeping element, the balance wheel. As the tuning fork would oscillate at a known frequency of 360 Hz, it would divide every second into 100 equal parts. This yielded accuracies of +/- 2 seconds a day. Not to be outdone by the Americans, Japanese engineers at Seiko released the first authentic quartz movement almost a decade later, in 1969. The movement was in the Seiko Astron, and while the watch was the same price as a family car, the demand was so high for it at the time that Seiko sold 100 units in its first week.

While quartz was only first released in 1969, Bulova released their Accutron model in 1960. This watch was powered by a precursor to the quartz movement, by passing a current through a tuning fork. It used this tuning fork to replace the traditional timekeeping element, the balance wheel. As the tuning fork would oscillate at a known frequency of 360 Hz, it would divide every second into 100 equal parts. This yielded accuracies of +/- 2 seconds a day. Not to be outdone by the Americans, Japanese engineers at Seiko released the first authentic quartz movement almost a decade later, in 1969. The movement was in the Seiko Astron, and while the watch was the same price as a family car, the demand was so high for it at the time that Seiko sold 100 units in its first week.

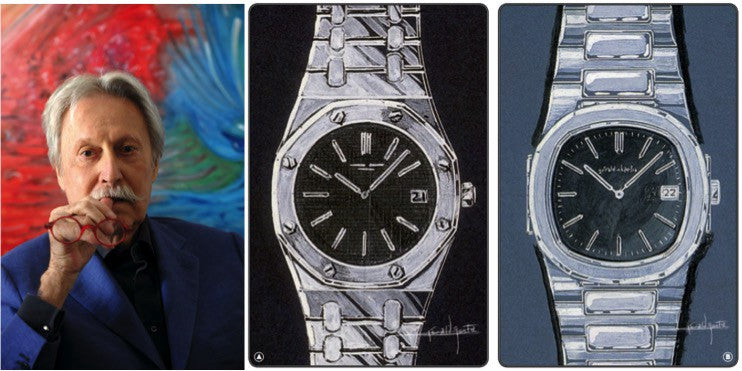

With the Quartz Crisis causing a significant amount of Swiss watchmakers to enter bankruptcy, the remaining brands had to pivot in other ways. Several Swiss brands formed a consortium to develop their own quartz movement, and some other brands released radical designs. It is widely acknowledged that if Audemars Piguet weren't in as weak a financial position as they were in 1972, due to the Quartz Crisis, that they wouldn't have released the Royal Oak.

The Tourbillon

Heralded as one of the most significant complications in Haute horology, the tourbillon exists as a way for watchmakers to display their horological heft, and elevate their timepieces from the ordinary to the incredible. Not as functional as they once were, the tourbillon has gone from a practical addition to a watch to an obsolete complication. This obsolescence hasn't stopped the tourbillon from having an incredible impact on watchmakers the world over, however, as we will explore.

Developed by Abraham-Louis Breguet in 1795, and patented six years later in 1801, the tourbillon's primary purpose was to mitigate gravity's effects on a pocket watches' movement. By their very nature, pocket watches are generally worn in a single vertical position, as they were worn hanging from a shirt. This pattern of use, coupled with flat storage, meant the average pocket watch movement was subject to unequal pressures due to gravity– in the hairspring to be precise, which disrupted their accuracy.

Developed by Abraham-Louis Breguet in 1795, and patented six years later in 1801, the tourbillon's primary purpose was to mitigate gravity's effects on a pocket watches' movement. By their very nature, pocket watches are generally worn in a single vertical position, as they were worn hanging from a shirt. This pattern of use, coupled with flat storage, meant the average pocket watch movement was subject to unequal pressures due to gravity– in the hairspring to be precise, which disrupted their accuracy.

The tourbillon was developed to solve this issue. It would rotate the escapement and balance wheel through all possible vertical positions, thus averaging the pressures of gravity on the movement. This is also where the name 'Tourbillon' came from, as it means 'whirlwind' in French and is a nod to the fact the tourbillion rotates around its own axis. The tourbillon reduced the number of positions an escapement might find itself from eight to just three; dial-up, dial-down and one vertical position. This greatly improved the pocket watches movement's accuracy and longevity as it prevented the hairspring from being deformed over time as gravity would no longer pull it down constantly.

While this might seem menial, at the time - it was not, as pocket watches were the only way to tell the time on the go accurately. Nowadays, tourbillons are no longer required for wristwatches as our hands' natural movements act like a tourbillon of sorts. Even though we don't need them anymore, tourbillons still fascinate watchmakers and collectors alike as this hyper-complex piece of engineering swings the escapement around in a kind of mechanical dance, remaining as a true stamp of true luxury and dedication to one's craft.

Automatic Movement

Before the 1930's practically every watch made would feature a manually wound movement. At the time wristwatches were in their infancy, and pocket watches would not be moved enough for automatic winding to make sense. While watchmakers had tried to develop creative solutions to create automatically winding pocket watches in the late 1700s, they were too expensive to build. Thus, they were never fully explored or commercialised. Wristwatches, with their constant movement, made automatic winding a reality and so, during the 1920s, development of automatic winding systems kicked into gear alongside the proliferation of wristwatch wearing.

While there were earlier attempts to create an automatic movement for the wristwatch by the likes of Leon Leroy, John Harwood and Leon Hatot in the 1920s, the most historically significant and commercially successful design was by Rolex in 1931. Building on the system that John Harwood created, Rolex manufactured a movement that had a centrally pivoting weight that could swing a full 360 degrees. This improved on Harwood's "bumper" design as his weight would only swing 180 degrees, to promote back and forth movement. Rolex's design also increased the amount of energy stored in the mainspring from a relatively puny 12 hours to a rather impressive 35 hours.

First delivered in their Oyster Perpetual model, Rolex' self-winding movement has been reimagined, reinterpreted and improved upon by several watchmakers since its inception almost 90 years ago. In 1948 Eterna developed a ball bearing system that could support a greater winding weight, thus improving the amount of force that could be created and in 2007 Carl F. Bucherer created a peripheral winding rotor that has allowed the development of incredibly thin automatic winding movements like the Bvlgari Octo Finissimo and Piaget Altiplano.

Long established as the gold standard for wristwatches, it is almost hard to find a luxury watch that is manually wound. While manual movements and all of the other kinds of movements are not going to become obsolete any time soon, automatic movements will continue to rule the roost and remain the most popular choice for watchmakers and collectors alike. With their improved convenience, it is hard to look past the humble automatic movement and appreciate they have come a long way and truly changed the industry for the better.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.